McLaren M6A-1

The Car That Ignited McLaren’s Winning Tradition

Foreword from Richard Griot:

It was March 3, 2009. I remember the day vividly.

After years and years of badgering Harry Matthews to sell me the M6A-1 and consistently being met with “I’ll never sell it”, I picked up the phone that day on a whim to try again. This time, however, I heard something new: “I’m ready to sell”. I was in the air the next day with my checkbook in my hand, giddy with anticipation for the meeting the next day. After sitting down across from Harry at his desk, he gave me his price and I jumped up to shake his hand and said “Deal”.

I managed to contain my excitement until I arrived at the airport, where out of nowhere I let out a holler and punched some air—turning heads from every angle—but I didn’t care. On March 5th, I was flying home as the owner of one of the most iconic race cars in history after years of pursuit and now it’s me who says, “I will never sell this car”.

In McLaren’s storied history, M6A-1 is in a class by itself and spearheaded the team to further expansion and conquering. The car has survived over the years, and was authentically restored back to the day it first raced at Road America in 1967—same engine block and all. Without the M6A, there may not be the famous “Papayas" on track today; the M6A is THE car that put McLaren on the map as a successful race team and propelled them beyond. The money coming in from the multi-year successes of winning in Can-Am gave McLaren the funds to develop the Formula One team. Today, Bruce McLaren’s cherished “Number 4” that adorned the M6A-1 and retains historical significance for McLaren, is still used on Lando Norris’s MCL60 today.

“To this day, the M6A-1 is one of my favorite cars to drive.”

Having driven other cars of that era, you can indisputably tell why the M6A's were so successful in 1967. Before acquiring the M6A-1, I had driven a Lola T160 that was nervous as hell and even took me airborne over Turn 1 at Laguna—I never felt comfortable in that car. But after the first shakedown in the M6A, it was obvious why Bruce Mclaren was leagues ahead in the 1967 CanAm Championship.

The best way to describe driving the M6A-1 is simply, neutral. Handling is light and responsive, but not aggressive in any way—you seem to float with the car around a track. When you miss an apex or get bent out of shape, the car provides plenty of warning to bring it back with little-to-no drama. It seems to take care of the driver in that respect. I’ve had the pleasure to drive it in many events up and down the West Coast and Road America, the latter being rather significant as the car today has the exact engine block used in qualifying when Bruce was there in ‘67. And yet, while driving the M6A-1 gives me ultimate happiness and enjoyment, it isn’t my favorite part of the car.

The emotion that it brings out in people is incredible and inspiring. I have endless stories of strangers approaching me to say they saw Bruce in the car in 1967 when they were kids, or that their parents had talked endlessly about seeing the famous dominance back in the day. Sharing and rekindling the spiritual bond that such an extraordinarily historic car can have, has been the best part of ownership.

“It has been an unbelievable honor.”

Today, it’s me that says, “I’ll never sell it."

Bruce McLaren

Born on August 30, 1937, in Auckland, New Zealand, McLaren developed a passion for motorsport at a young age. He began racing in local events, showcasing remarkable talent and determination.

In the late 1950s, McLaren caught the attention of racing icon Jack Brabham, who invited him to join the Cooper Racing Team in Formula One. At the age of 22, Bruce became the youngest driver to win a Formula One race when he triumphed at the 1959 United States Grand Prix.

During his time with Cooper, McLaren established himself as a skilled driver and an innovative engineer. However, his desire to build his own cars led him to establish Bruce McLaren Motor Racing Ltd. in 1963. The team initially focused on building sports cars and began competing in international sports car races.

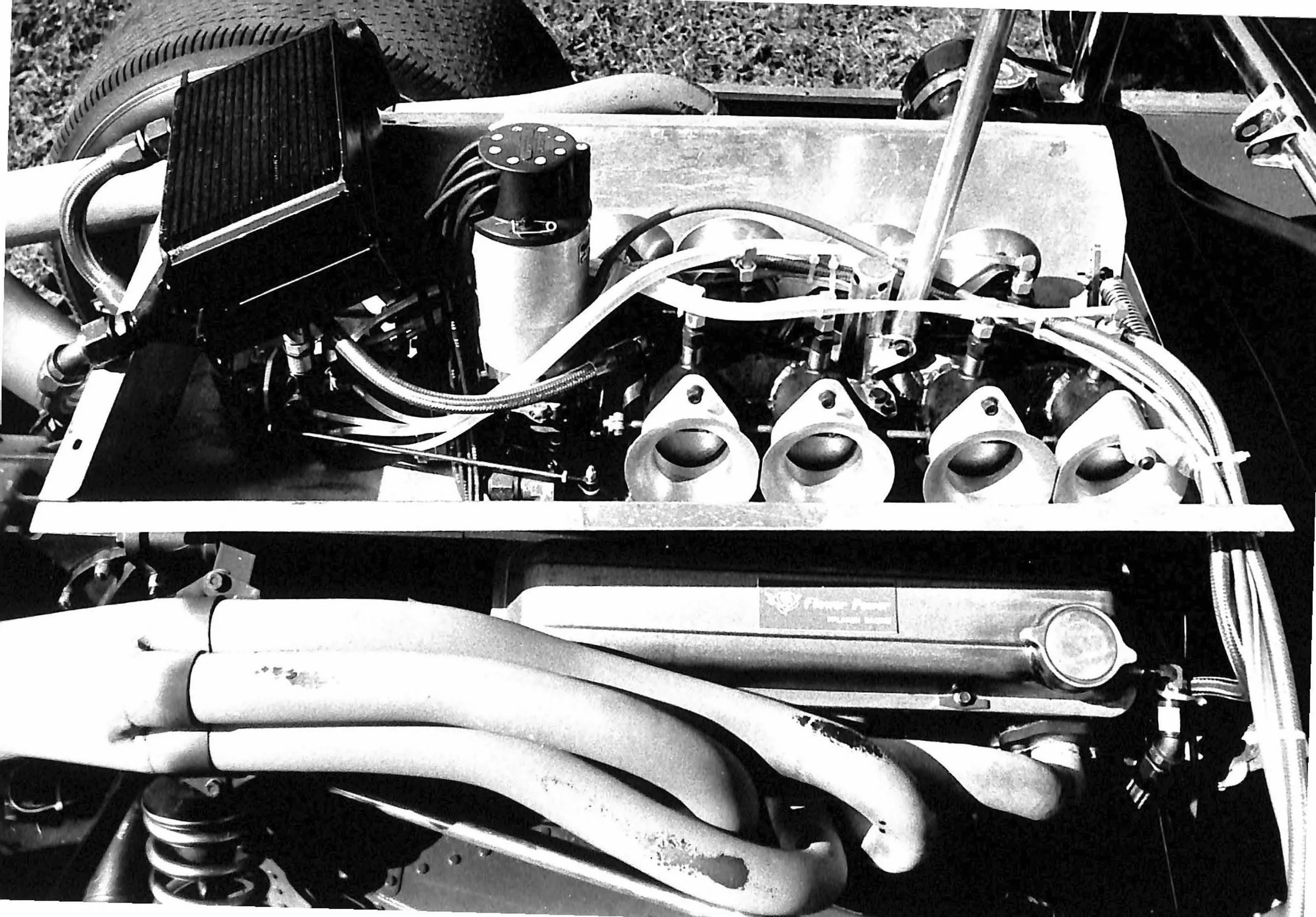

The result was the McLaren M6A, introduced in 1967. Designed by McLaren and his team, the M6A was a revolutionary car, featuring a lightweight aluminum monocoque chassis and a powerful Chevrolet V8 engine. The sleek and aerodynamic design provided exceptional speed and handling capabilities with the engine mounted in front of the rear axle to ensure better weight distribution. This modern construction allowed the driver to easily handle all 525 horsepower—unlike its predecessors. Driving it was more like a dance than a fight.

The M6A-1 made its debut in the 1967 Can-Am season and immediately showcased its dominance. Driven by McLaren himself, the car won five out of the six races that season, securing the driver's championship for McLaren and the constructor's championship for his team, alongside Denny Hulme in the M6A-2.

The success of the M6A continued in the following years, kicking off what is known as “The Bruce and Denny Show”, with McLaren winning the Can-Am championships in 1968 and 1969 as well. The M6A, along with subsequent variations like the M6B and M8A, established McLaren as a force to be reckoned with in the Can-Am series, dominating the competition for several seasons.

Bruce McLaren's vision, engineering prowess, and driving talent played a crucial role in the success of the M6A and the subsequent McLaren Racing team. Tragically, on June 2, 1970, Bruce McLaren lost his life in a testing accident at the Goodwood Circuit in England. Despite his untimely death, his legacy lives on through McLaren Racing, which has become one of the most successful and iconic teams in Formula One history. The M6A remains an iconic car in motorsport history, symbolizing Bruce McLaren's engineering genius and the team's dedication to innovation and excellence.

Can-Am

What began as a one-off, ad-hoc exhibition for stateside European drivers wrapping up their seasons with Grands Prix in North America, turned into a full-fledged race series with no holds barred. In typical American fashion, the Canadian American Challenge Cup, more commonly known as the Can-Am Series, was loud, brash, and had a deluge of money. Bruce saw this not only as an opportunity to fund his dream of owning a Formula One team, but to flex his expertise in creating the superior driving machine in a series that lauded it’s lack of restrictions. With a total of $358,570 USD in 1966 for total prize money, this series had more to winnings than any other and therefore attracted the best of the best to compete.

While it did not have the gravitas and tradition that other series carried, it drew in the biggest racing names of the time from Formula One, Indy-Car, endurance racing, NASCAR, and NHRA. This includes renowned drivers like Mark Donohue, Denny Hulme, George Follmer, Peter Revson, Vic Elford, A.J. Foyt, Parnelli Jones, Graham Hill, Phil Hill, David Hobbs, Bob Bondurant, Jackie Stewart, Mario Andretti, Jackie Oliver, and Dan Gurney.

The series today is thought of as dangerous and radical, but it also pioneered technology that is still used in its evolved form; Can-Am cars were among the first to use wings, turbocharging, ground-effect aerodynamics, and aerospace materials like titanium. While the expensive materials and research led to the eventual downfall of the series, Can-Am cars were at the forefront of racing technology and were frequently as fast as or faster around certain circuits than the contemporary Formula One cars.

So when the previously lackluster McLaren team rolled out the original papayas in the paddock of 30 cars, they were met with skepticism and awe. But Road America was their first comparative look to the rest of the pack and the restored M6A-1 today is fitted with the same engine used by Bruce that fateful weekend.

Building the M6A

The McLaren racing team was unique from the start—Bruce McLaren not only owned the team and raced the car, he also had a hand in the design and development of the machines he sat in. Sitting behind the wheel of his own creation with the mind of an engineer allowed him to recognize small sensations in the car, communicate these to the team, and help in resolving any issues. This is a huge reason of how they were famously able to build the M6A-1 from drawings to a working prototype in just 11 weeks leading up to the 1967 Can-AM season. But he didn’t do it alone—Bruce knew that if wanted a superior car, he needed the best minds in the world to collaborate.

In early 1967, Bruce recruited the top minds from the racing ecosystem and beyond to help achieve his dream. His team included Formula One drivers Denny Hulme and Chris Amon, future managing legend Teddy Mayer, Aeronautical Engineer Robin Herd, and a slew of multinational mechanics such as Tyler Alexander, Haig Alltounian, Alan Anderson, Tom Anderson, Tony Attard, Roger Bailey, Colin Beanland, Leo Beattie, Don Beresford, George Bolthoff, Alistair Caldwell, Chris Charles, David Dunlap, Donny Ray Everett, Alec Greaves, Vince Higgins, Gary Knutson, Alan McCall Lee Muir, Jimmy Stone, Cary Taylor, and Frank Zimmerman.

Aero

At the beginning, Robin Herd, Gordon Coppuck, Tyler Alexander, and Don Beresford laid the monumental groundwork and constructed the foundation for the M6A’s monocoque bodywork and chassis. Learning from the 1966 Ford J-car that had produced far too much drag at Le Mans, McLaren realized this inherent downforce could be utilized in Can-AM’s short, snaking circuits. By focusing on ground effect—a method of increasing the downforce of a car by creating a vacuum-like atmosphere underneath—the M6A was able to take corners at higher speeds than previous iterations.

Engine

Gary Knutson was a development engineer with Chaparral when he met the McLaren team during the Can-Am season, leading him to eventually work for both teams. After taking over McLaren’s engine program in 1967, he began to work with Al Bartz at TRACO in Van Nuys, California, as they were without at dynamometer in England and had previous collaborated with Bartz in the past.

The famous Flower Power Mclaren Chevrolet were prepared by Bartz, and then assembled by team mechanic Gary Knutson. These engines were among the most successful in racing story, completely dominating the CanAm series and the USSRC for several years. They made some troubles for Bartz because other customers would ask why the Mclarens were so much faster. Bartz would then pull out the dyno figures that showed a maximum difference of six horsepower or around one percent.

The McLaren 350 Chevys initially produced about 525 hp at 7,000 rpm with a compression ratio of 11.2-to-1, but back in England, Knutson began thinking outside of the engine block. Inspired by Lucas fuel injection systems in its Formula series engines, he contacted their aerospace division and was met with horrified Brits. The thought of their fuel injection systems going into an unsophisticated, unregulated car like a Can-Am was daunting—but not quite enough to stop them from dropping off a ratty cardboard box of spare parts. the eight-cylinder MKII metering unit, fuel pump, and a set of injectors were McLaren’s, but they had to figure the rest out on their own.

While all of that work for a rudimentary fuel injection only added about 25 hp, it did improve throttle response and driveability in the M6As and paved the way for further advancements down the line.

Pre-Season Testing

After the McLaren team decided to prioritize Can-Am over Formula One development following a series of setbacks, delays, and underfunding, the M6A was completed and ready for testing on June 19—over three months before the start of the season. They then took the car to Goodwood, a track in Southern England that had a similar layout to those in North America, and with the intention of running it into the ground.

It immediately garnered attention and sparked conversation on how it would perform before even hitting the track. The M6A had several significant features that hadn’t been seen before—the steep nose angle, the low nose clearance in front of the wheels, the lack of rear wing, the small adjustable spoiler, the slick-surfaced cockpit, and novel suspension. The fact that the passenger seat was built into the car to fit regulations and not actually be a seat was especially unfathomable.

At Goodwood, they worked out all the kinks, fine-tuned the car, and drove it to failure (or tried to) as much as they could. The best test time around the track earlier in the season had been John Surtees in his Lola at 1:16 and the previous Can-Am McLaren, the M1A, had completed its best lap at 1:18. Bruce began a 200-mile destruction test in the M6A without the body fitted—a purely mechanical test without any downforce—and was lapping consistently at 1:16. Suffice it to say, they had a racecar.

Next came the aero tests. Robin Herd, sitting shotgun with an anemometer, was tracking the air pressure underneath the car when Bruce took an initial lap with the newly installed bodywork. McLaren took a corner at near full speed and the meter dropped to zero. When they finally came to a stop Bruce turned to Robin and said, “No one can know about this”, he knew he was sitting on the industry’s best kept secret. By the end of their full-speed sessions, Bruce and Denny’s times were 1:13.9 and 1:13.4, respectively—two seconds quicker than the record set by Brabham’s Formula One car.

After logging over 2,000 miles of development driving around Goodwood, they felt they were ready to compete in Can-Am and finally get a win following their disappointing ‘66 season. Now all they needed was a quick coat of paint and they were headed to Wisconsin.

M6A in Can-Am

Road America - September 3, 1967

The boys made their impression quickly in the second inaugural season of the Canadian-American Challenge Cup, with their first race in Elkhart, Wisconsin, marking the start of McLaren historic era of dominance.

The two papayas were in a league of their own from the start of qualifying. Bruce set the top qualifying lap of the field at 2:12.8, ten seconds better than the previous lap record, and one-tenth better than Hulme. However, Denny went on to set a new race lap record and won the 200-miler at an average speed above any previous single-lap mark, finishing at an astounding 93 seconds ahead of the next car. The man he beat was the recent USRRC champion, Mark Donohue, and the defending Can-Am champion, John Surtees, was an even more distant third in his Lola.

The McLarens had made a serious statement. But did the team, the drivers, and the car all have the stamina to go five more races?

Chevron Grand Prix - September 17, 1967

By the second race, it was already clear that the twin McLarens of Bruce and Denny were in a class by themselves. After dominating qualifying—with Hulme in P1 this round after setting the new record—the bright orange monsters shot off the grid and never looked back. Scratch that, Hulme had a mid-race spin—presumably to check out the competition behind—and still managed to finish ahead of his boss.

McLaren secure their first of many double podiums, with Denny and Bruce taking a bow in front of the pack.

“Once again it was a McLaren ball game and no one else was even dressed for the game!”

Don Grey, Motoring News

Player’s 200 - September 23, 1967

Mosport resulted in a similar weekend as the previous race, but with a little more spice. With only five days to travel, prep, and practice, teams were scrambling to not only to compete with the McLarens, but just to race at all. The field was a mess with crashes, breaks, shunts, leaks, failures, and dropouts throughout practice and qualifying, giving the third race of the season an air of chaos. While Hulme set the record lap time, race time, lap speed, and led every lap, the McLarens were not as intimidating at Mosport as the pack caught up a bit, with Dan Gurney tying Bruce’s qualifying time of 1:21.1.

Any rival looking for a chink in the McLaren armor must have thought they saw it just before the race, in the form of a leak in one of Bruce's fuel cells. But the Kiwi’s team plunged into a bag-change that normally took ninety minutes and completed the job in a reported forty-five. By then, the remainder of the field had started the pace lap, and Bruce charged off after them to assume his position in P2 before the green flag dropped—but he didn’t make it. Bruce saw the rolling start from dead last.

While Hulme streaked off into the distance, creating a 27-second cushion to Gurney by lap 20, McLaren picked up eight places in five laps. Four laps later he was in 13th. On the 12th lap he picked up three more places and by lap 14 he was in seventh place. At the halfway mark of 40 laps, he was in third, having passed 27 cars and only Gurney standing between Bruce and second place. With 16 laps to go, Gurney ran into backmarker traffic and McLaren closed to two car lengths, allowing him to put two wheels in the dirt at turn three and sneak past to put the cherry on top of an all-time drive. By the end of the drive, he had also lapped the entire field—spare his teammate of course.

But the race wasn’t quite appeased with the drama thus far. With just a lap to go, Hulme’s steering rack became loose and sent him off-track, into the embankment, shoving the bodywork into the left front tire and puncturing it. He limped to the finish line with the tire flat and jammed to a stop, smoking up a storm, winning McLaren’s third race in a row in memorable fashion.

"As McLaren nosed his way forward through many of the back markers he seemed to be handling the big car as though it were a Formula I machine, taking almost any line he chose. Gurney's car was obviously no match for the new McLaren as he was consistently out-handled, out-braked, and out-accelerated everywhere on the course." - Bob MacGregor, Autosport

Monterrey Grand Prix - October 15, 1967

For the first time in the season, the McLaren’s were not together on the first row. Denny’s car was with hit with a list of abnormalities with his ignition, fuel injection, broken brake pedal, and cracked wheels, which landed him 0.1 second behind the qualifying time of Dan Gurney—seemingly the only man that could make any sort of stand against the McLarens.

Because of the starting grid, Leguna Seca was also the first time in the season where a non-McLaren car led the race…for eight laps. After a breakdown with Gurney’s Ford, Bruce cruised past and created some distance to the rest of the pack while Denny played defense.

With the hot California sun beating down on him and the uninsulated cockpit, Bruce was driving an oven—a very fast oven. In a coordinated effort, he stopped his car on-track next to the pit wall, got out, and had a bucket of water poured over himself by a crewmember. But with the gap he had created he had plenty of time to hop back in his car and get back to leading the race. By the time he saw the checkered flag, he had lapped the entire field, set lap records, and was now just five points behind his teammate.

This race also marked the start of Ferrari’s foray into the Can-Am series, with Chris Amon and Jonathan Williams entering in their 4.2 liter, 36-valve, V-12 P4s. They finished in fifth and eighth—a respectable feat for the first race, especially considering the heat knocked out two-thirds of the grid with only nine cars finishing.

Times Grand Prix - October 29, 1967

The Times Grand Prix had the largest sum of winnings on the calendar, giving teams extra motivation to finish as close as they could to the McLarens—winning seemed out of the question without a double retirement. Local favorite, Dan Gurney, had a flyer of a qualifying lap and placed his car in pole position after beating Bruce McLaren’s time by a mere 0.3 seconds. Hulme’s best lap was 1.3 seconds behind Gurney, sticking him in the third slot to start for a consecutive race. It was clear that the high speed nature of the track was going to be a challenge for the smaller engines of the M6A.

As at Laguna, Gurney beat McLaren into the first turn, and Jones again charged up to take third. Hulme dropped back behind Andretti and Hall, unfortunately putting him in just the right spot to hit a tire apex marker that had been torn loose in turn eight. The impact shattered the McLaren’s left front fender and forced Denny to pit for a little vehicular surgery. But as he tried to rejoin the race, the official at the pit exit stopped him, saying there wasn't enough of the fender remaining to comply with the bodywork integrity rule.

The Bear threw it in reverse and blasted backward down the pit lane to discuss with the officials by the start-finish line—an image that would make modern-day FIA and racegoers gasp. But after pleading his case saying it wasn’t his fault, he was disqualified and turned spectator for the remaining 60 laps.

Lap three, Bruce finds himself in second place when Gurney has engine problems and retires the car. Then Jim Hall started closing on McLaren. This set up the best Can-Am racing of the season and one of the best ever. Never mind that every other potential contender fell back or out with the standard litany of Group 7 disasters; never mind a mid-race gale that blew up a desert sandstorm: the two leaders were running a Grand Prix.

That's how the race played out, the Chaparral chasing down the McLaren. Until a little over half-distance, Bruce had to avoid two spinning backmarkers to avoid what would have been significant crashes. Jim pounced after the second instance, and his tall, white wing waggled triumphantly as he was finally in the lead of a Can-Am race. He held it until McLaren out braked him at the end of the long back straight, but then Bruce ran afoul of more traffic, and the Chaparral whipped by again.

Hall, his flipper wing visibly giving the big-block better traction off the turns, was able to stave off McLaren for a few more laps, but then the orange car squeezed back in front. This time McLaren kept it there, though he had to keep his little Chevy engine in the red to do it. The gap at the checkered flag was a mere three seconds.

"The other chaps are catching up!" Bruce noted, wiping his brow.

The win had moved Bruce into the lead position of the series with just one race left, but the gap—just a few points—meant it was either McLaren driver’s championship to secure.

Stardust Grand Prix - November 12, 1967

With the McLaren’s each having twice as many points as their next best contenders, the Can-Am Championship came down to the two drivers. Bruce was three points up on Denny and after qualifying, it was looking like it was Bruce’s to give away. Holme experienced a broken valve rocker that dropped his time and placed him in P5 to start the race, while McLaren set the lap record of 1:30.8 and secured the pole.

After a questionable rolling start where Parnelli Jones crossed the start line in first position, giving him a three-second lead by the end of the first lap, there was a dust-up in the minefield. This caused Denny to have a puncture and pit, placing him at the back of the pack. Soon after, Bruce retired with a anticipated engine issue that couldn’t be dealt with pre-race. That meant Denny just needed to finish in fourth to claim the trophy.

He set off weaving through the pack, picking them off one by one. After a stunning 51 laps, he had captured the fourth position and could cruise his way to a victorious season—but his luck ran out. The infallible, reliable Chevy engines that together won every race in ‘67 thus far, broke down and Hulme’s car came to a rest in front of the pits and grandstands.

Bruce had won the second Canadian American Challenge Cup and would go down as one of the most dominant seasons in racing history.

M6A in the USRRC

After securing the 1967 Can-Am Championship, McLaren enlisted Trogan to manufacture similar cars—the M6B—for privateers, but the M6A wasn’t obsolete yet. Not even close. After finishing third in the 1967 Can-Am series, Mark Donohue stepped into the freshly painted car that was bought by Penske and continued to solidify the McLaren in its supremacy.

Sporting the new blue “Sunoco Special” car with a newly installed 427 CID Aluminium Chevrolet engine, Donohue dominated the circuit. While Donohue had to retire the car in four of the nine races, he secured the championship outright by winning every race he finished. He set the fastest lap at each of these races and led every single lap—once again displaying the superiority of the M6A.

1968 USRRC Season

Mexico City - March 31 - DNS

Riverside - April 28 - First Place

Laguna Seca - May 5 - First Place

Bridgehampton - May 12 - DNF

St. Jovite - June 2 - First Place

Pacific Raceways - June 30 - DNF

Watkins Glen - July 13 - First Place

Road America - July 28 - DNF

Mid-Ohio - August 18 - First Place

Four drivers won races during the season and there were three drivers who had a shot at the title going into the last race.

Mark Donohue took his first win of the season. At Laguna Seca, Jim Hall won the pole again, and this time was able to start the race. In his last USRRC appearance, Hall brought the ill-handling Chaparral home in third place. Donohue scored his second victory at Laguna Seca and followed it with wins at St Jovite, Watkins Glen and Mid-Ohio. Skip Scott won the high attrition races at Bridgehampton and Pacific Raceways. Plus he shared the win at Road America with his teammate, Charlie Parsons.

The Laguna Seca race provided the closest finish, with Lothar trailing Donohue by three-quarters of a second. Skip Scott's two victories were by three seconds and six and a half seconds. It looked close. Their shared win at Road America was the greatest victory margin of the year at six laps, or twenty-four miles.

The 1968 USC season set records for attendance and prize money paid out. Paid admissions grew from 171,725 in 1967 to 210,000 in 1968. Prize money went from $109.750 to $186,000. Contingency money provided by oil, tire and accessory suppliers topped $45,000. Plus there was a $15,000 championship point funds for the top ten finishers.

There were a total of 219 individual starters for the nine races. Skip Scott and Charlie Parsons were the only drivers to compete in all nine races. Mark Donohue, Lothar Motschenbacher and George Eaton made eight races. Sam Posey and John Cannon started seven races while Bud Morley and John Cords took in six races. Four other drivers started five races and six drivers started four races. Twelve drivers started three races and fifteen drivers started in two races. That left 173 drivers starting just a single race. Of the 219 starters, only 39 were under two-liters.

By the end of the series, it was known that this would be the last season for the USRRC series. The SCCA wanted to expand the Can-Am series and the only way to do that was to start earlier in the summer. Their professional formula car series was showing tremendous potential. Giving it the promotional attention it needed just didn't leave room for the USRRC. It died a quiet, sudden death.